”Train yourself to let go of all the thing you fear to lose”. ‘

Yoda

Fear of mortality can be found across every culture and every era; pyramids in ancient Egipt, jade burial suits in China, a panacea in middle ages Europe, cryonics facilities in 1960’s USA, were all created as a ”solutions” to the problem of human impermanence. Western societies become so accustomed to excesses choice of information (Collins, 1995) and sensation that vision of not participating and not experiencing anymore is becoming not only frightful but also unacceptable. According to Marshall McLuhan (1994) “… after more than a century of electric technology, we have extended our central nervous system itself in a global embrace, abolishing both space and time as far as our planet is concerned.” We want to believe that even if we cannot stop the process of dying, our existance can become somehow pemament. Articles in pseudoscientific publication fuel these assumptions boldly claiming among the other that ”Humans will achieve IMMORTALITY using AI and genetic engineering by 2050.”(Daily Mail).

Tokyo’s High-Tech Cemetery

This idea also is broadly investigated in many different forms by popular culture production. To mention some of the most widely recognised examples, we can remind Transcendence (2014) or Be Right Back (Black Mirror, 2013). In both of those examples, a dead lover is ”reincarnated” through an online avatar, which is possessing memories of its ”previous life”. Many scientists (Hauskeller, 2012)(Choe, Kwon, Chung, 2012) have been speculating about the possibility of mind uploading in the face of fast developing scan technology and cheaper hardware. However, as the present day, this technology is only existing in science fiction novels, which by no means restricts the creativity of enterprises.

Transcendence (2014)

We can already access a wide range of more conventional post-mortem digital services. From companies like Last Pass providing safekeeping of multiple passwords and nominating online power of attorney, through My Goodbye Message sending final personalised messages to earlier designated contacts, to Safe Beyond recordings videos celebrating important moments after our departure.

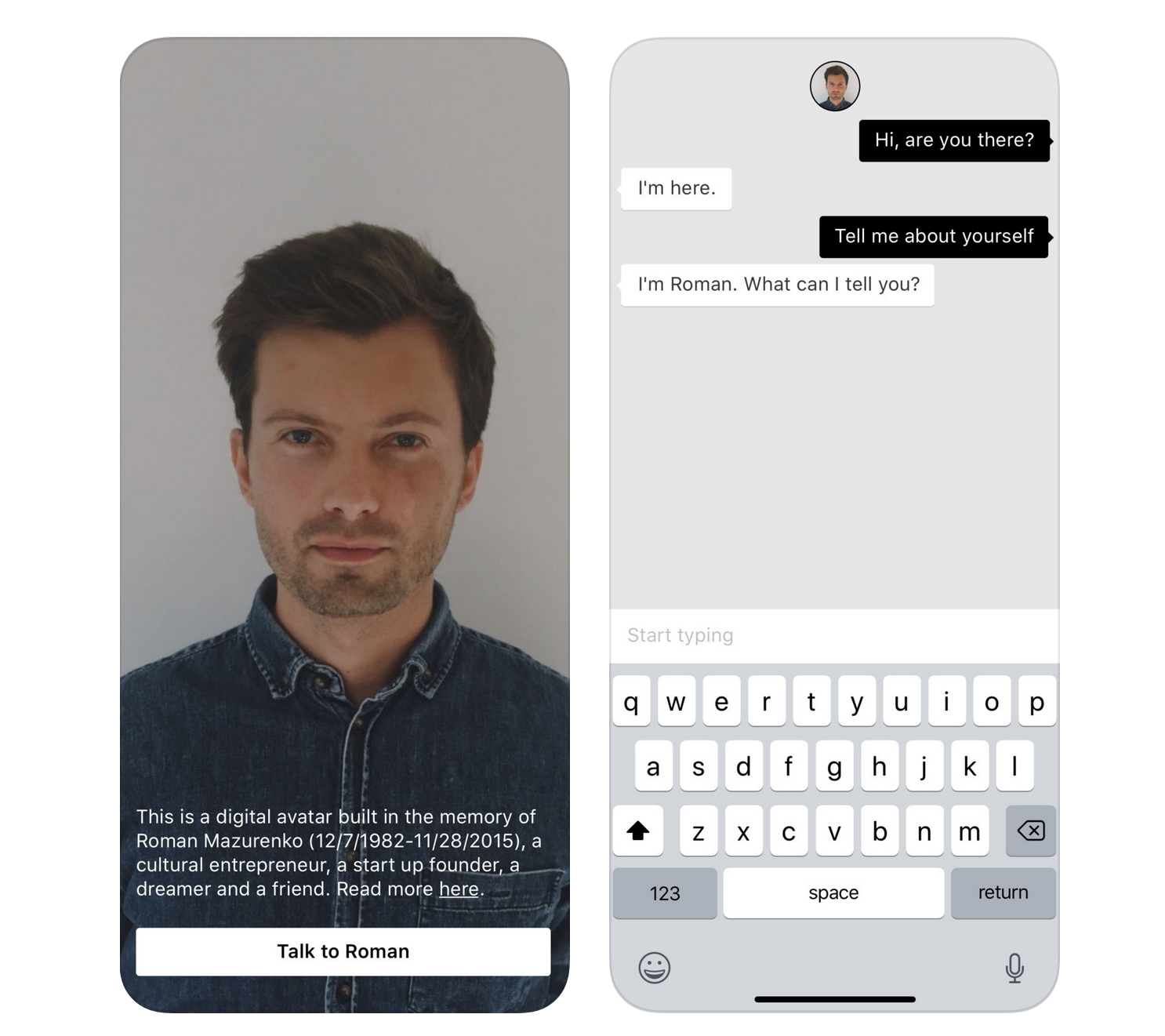

The more controversial approach is presented by companies like Eterni.me, which are trying to not only preserve but, also recreate the dead person. In order to do that posts and social media activity is collected to creat a sample of deceased’s personality that is then loaded onto an online software trying to emulate their behaviours. As described by Marius Ursache, co-founder of, Eterni.me

”The service’s defining feature is a 3-D digital avatar, designed to look and sound like you […] A user will be encouraged to “train” its avatar, through daily interactions, in order to improve its vocabulary and conversational skills.”

It is easy to notice that there is plenty to unpack in this concept; ”training” oneself avatar is a disturbing way of curating our legacy (Bellamy et al, 2013). The act of creating an online avatar is almost like the embalming process, where the aim is to preserve the dead person for all cost. It is based on the false idea that, as a society, we can somehow defeat death and decay. It is deeply rooted in our fear of entropy, a conviction that lack of control is evidence of failure. However, it would be profoundly misleading to blame individuals for such a situation. Sanitised and beautified society of the western world do not prepare to accept the inevitable mortality of all living organisms (Kellehear, 1984), dead members of the community are ignored and quickly forgotten. Families are postponing their grief using digital space instead of embracing the gruelling experience.

The idea of online immortality raises the broad problem of ownership of oneself. When technology is allowing us to recreate not only somebody’s image but emulate behaviours, voice and body movements, we can ”resurrect person” for commercial use. We can ”force” them to participate in projects that they would not support while being alive, include them in another episode of never-ending franchises (Paul Walker in Furious 7, 2015) and profit of the latest merchandise appropriating their imagery. This thought leads us to multiple controversial issues of monetarizing on deceased people imagery, power attorney of online avatars, right to be forgotten, and many more.

To better understand the benefits and disadvantages of ”ressurected avatars” technology I chose to interact with a digital memorial of Roman Mazurenko. It was quite an engaging experience for a brief time creating a mimetic impression. Nonetheless, “It’s still a shadow of a person” as addmits bot creator Eugenia Kuyda, I have to agree that after a while limitations of the machine were becoming painfully obvious. As a present day, software programs are lacking creativity and self-awareness; all their actions are an outcome of their algorithms. Thus, Roman’s avatar is only what his friends wanted him to be. It is just a mere memory ”of a startup founder, cultural entrepreneur, dreamer, son and friend” but not a Roman himself.

https://www.netflix.com/gb/title/70264888 https://www.amazon.co.uk/Transcendence-Johnny-Depp/dp/B01DY1U6SC/ref=sr_1_1?crid=Q1OIT8JKAOEZ&keywords=transcendence+film&qid=1554842339&s=gateway&sprefix=transcendence+f%2Cstripbooks%2C134&sr=8-1 https://www.theverge.com/a/luka-artificial-intelligence-memorial-roman-mazurenko-bot https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/29/health/29grief.html https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-5408425/Human-beings-achieve-immortality-2050.html

Bellamy, C. Michael, A., Martin R. Gibbs, R. M., Nansen, B., Kohn, T. (2013) Life beyond the timeline: creating and curating a digital legacy. In: CIRN Prato Community Informatics Conference, Oct 28-30 2013, Monash Centre, Prato Italy Belshaw, C. (1993) Asymmetry and non-existence. In: Philosophical Studies, Vol. 70, Issue 1, pp 103–116

Choe,Y., Kwon, J., Chung J. R. (2012) Time, Consciousness, and Mind Uploading. In: International Journal of Machine Consciousness,Vol. 04, pp. 257-274 Collins, J (1995) Architectures of Excess: Cultural Life in the Information Age, 1st edition, Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge Doughty, C. (2017) From here to eternity, London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson

Hauskeller, M. (2012) My brain, my mind, and I: Some philosophical assumptions of mind-uploading. International Journal of Machine Consciousness, Vol. 04, pp. 187-200

Kellehear, A. (1984) Are we a ‘death-denying’ society? In: Social Science & Medicine,Vol. 18, Issue 9, pp. 713-721 Mcluhan, M., Lapham, L. H. (1994) Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man The

Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press

Moreman, C., Lewis, D. (2014) Digital Death: Mortality and Beyond in the Online Age

Santa Barbara, California: Praeger